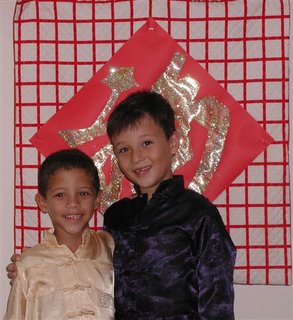

Maureen and I have been reading a book called Boundaries with Kids by Henry Cloud and John Townsend. I’ve found a lot of very practical help in the book in dealing with my kids, such as empathizing with their frustrations and yet setting clear boundaries. Yesterday, the kids had a friend over after school to play. When dark and supper time drew near, I told them that I would need to take their friend home. Jonathan, my youngest, did not like that idea at all. I cut off his protests and explained to him that it also made me sad when my friends had to leave, but that if he didn’t straighten up, then his friend would not be able to visit next time. Knowing that I was serious, Jonathan accepted reality and went inside. When I returned from taking the friend home, Jonathan had already had his bath and was ready for supper.

OK, so it’s not exactly the wisdom of Solomon, but I do appreciate the practical help.

Another principle in the book is that parents should look for ways of discipline that hurt, but do not harm, the child. In the early years, that may be “hurt” that the parent physically applies to the child. As they grow, the hurt comes from structuring consequences that come from the child’s own choices, and allowing the child to experience them. It’s hard to see your child hurt, but they will not learn self-discipline without experiencing pain.

Hurt, however, is not the same thing as harm. Children should be allowed to experience hurt, but it is the parents’ job to protect them from harm, and certainly to never do anything that would harm the child physically, emotionally, relationally, or spiritually.

I’ve been reading about the resurrection of Lazarus, and I’ve been intrigued with Jesus’ delay in coming to Bethany, where Mary and Martha had been waiting for him to show up and heal their brother. Have you noticed that, when Jesus does finally arrive, Mary and Martha both greet Jesus in the same way? “Lord,” they both say on separate occasions, “if you had been here, my brother would not have died” (John 11:21, 32). It sounds like they had been saying this to one another -- “If Jesus would just show up, he could heal him. If Jesus had come, none of this would have happened. We called for Jesus. Why hasn’t he shown up?”

Maybe you’ve felt the same way. Maybe you’ve called for Jesus, but he hasn’t shown up. Why does he let you hurt so badly?

Jesus knew that he intended to do something much greater than healing Lazarus – he was going to raise him. But he also knew that in order for that to happen, his friends had to hurt. But what keeps this from being a cruel manipulation is that Jesus was hurting, too. In his commentary on John, F.F. Bruce translates that Jesus “shook with emotion” and “burst into tears” (John 11:33-37, p. 246). In her earlier confession that Jesus was the “Messiah” and the “Son of God” (John 11:27), Martha had been exactly right. But Jesus was also the Son of Man. Even more than it hurts me to see my kids hurt from the consequences that I impose on them, it hurt Jesus deeply to witness the pain of others – especially pain that he himself had caused.

But Jesus would not allow his friends to be harmed. As he had already told Martha, “I am the resurrection and the life.” In Jesus, even death is not ultimate and so, in spite of death, no ultimate harm can come to the believer.

Jesus allows—sometimes even causes—us to hurt. But because he is resurrection and his is life, he always protects us from harm.